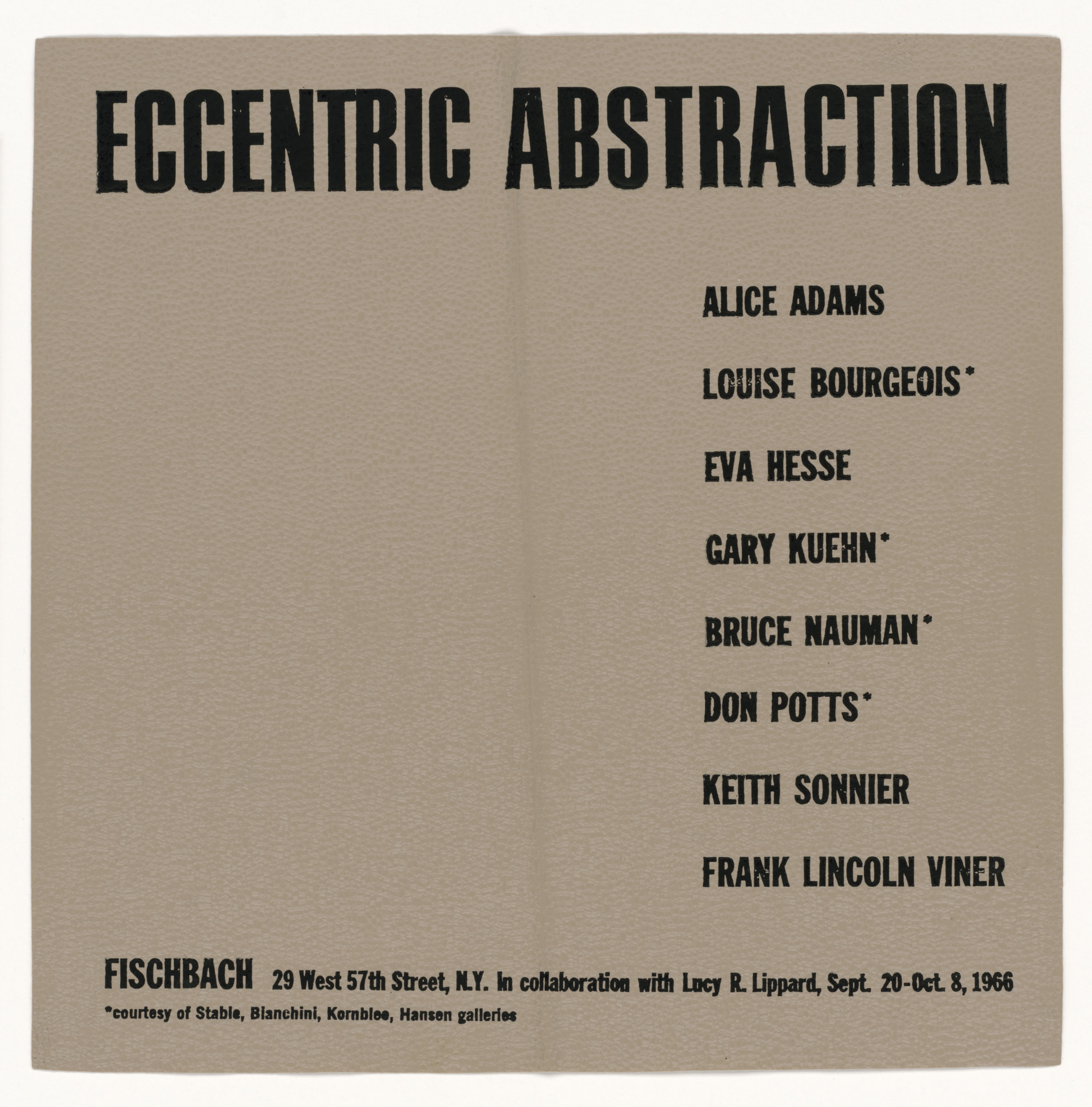

ECCENTRIC ABSTRACTION, Fischbach Gallery, New York, 1966

Artists: Alice Adams, Louise Bourgeois, Gary Kuehn, Eva Hesse, Bruce Nauman, Don Potts, Keith Sonnier, Frank Lincoln Viner

Curated by: Lucy Lippard

Opening: September 20, 1966

Duration: September 20–October 3, 1966

Dimensions: 26.2 x 26.3 cm

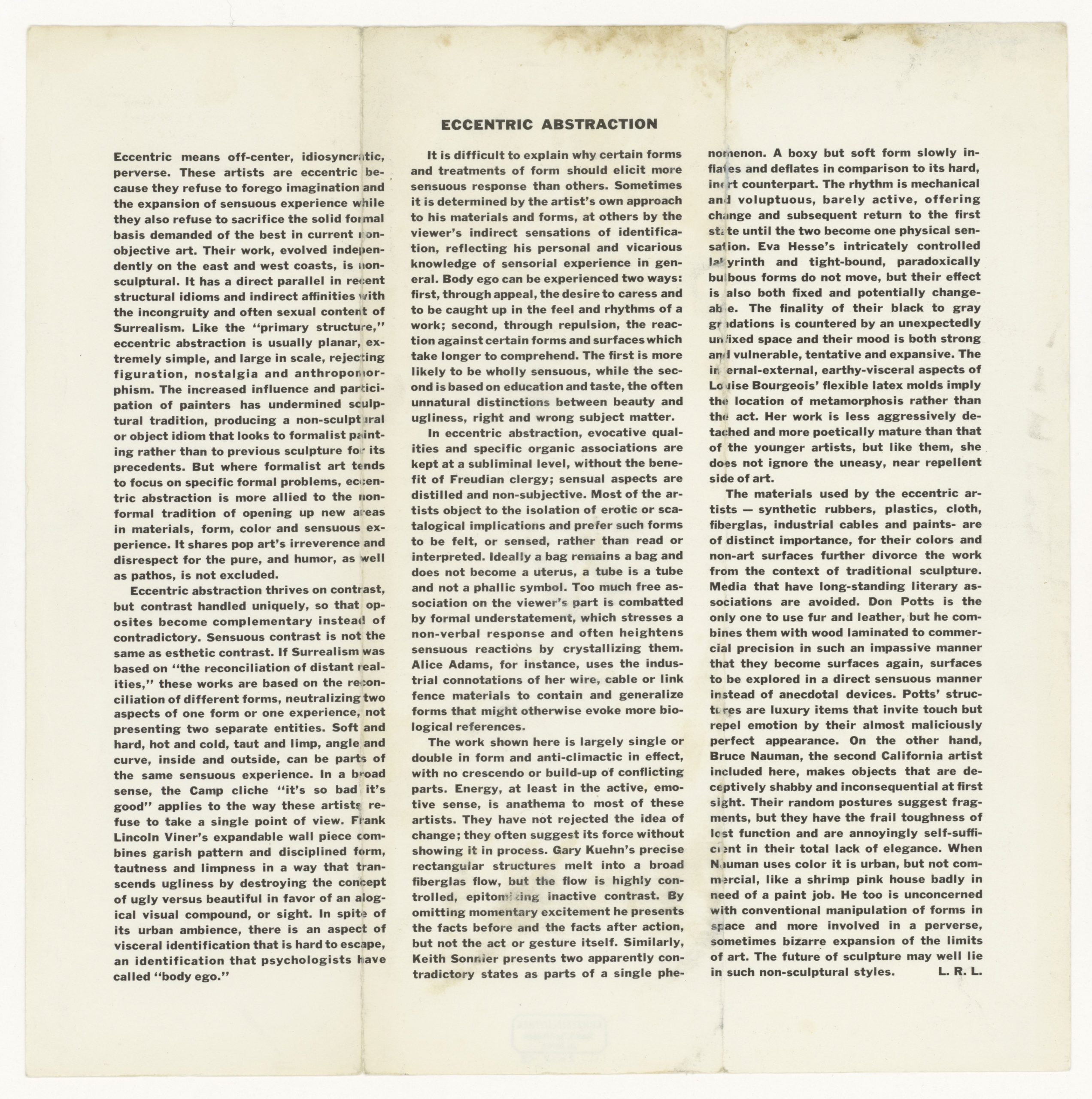

Further Information: Foregrounding materiality over image, the invitation card for Eccentric Abstraction mirrors the participating artists’ emphasis on the suggestive capacities of material surfaces and textures. Eccentric Abstraction was the first independent curatorial project of the North American writer, art critic, curator, and activist Lucy Lippard and “an attempt to blur boundaries … between minimalism and something more sensuous and sensual.”[1] The softening of boundaries becomes also evident in the densely-written, manifesto-like text on the back of the invitation card, in which Lippard sets out her concept of “Eccentric Abstraction,” locating her position between curator and art critic. In her essay, Verena Kittel introduces the idea that the blurring of boundaries manifesting in the artworks presented in Eccentric Abstraction between art and life, i.e. the aesthetic and the extra-aesthetic sphere of an artwork,[2] provoked experiences of antagonisms that have become characteristic for Lippard’s future practice in the 1960s and 70s.

Eccentric Abstraction took place from September 20 to October 8, 1966, at Marylin Fischbach’s gallery in New York. The works presented in the show by the artists Alice Adams (*1930), Louise Bourgeois (1911–2010), Eva Hesse (1936–70), Gary Kuehn (*1939), Bruce Nauman (*1941), Don Potts (*1936), Keith Sonnier (*1941), and Frank Lincoln Viner (*1936)—most of them in their late 20s or early 30s, and, except for Louise Bourgeois, not very well-known at the time—were characterized by the use of non-specific forms and an emphasis on the tactile surfaces and textures of materials, as well as their evocative, sensuous qualities. Alongside the exhibition, an article with the same name was published in Art International, providing the basis for Eccentric Abstraction.[3] Lippard intended to spark a discussion about artistic positions beyond dominant trends in minimalist sculpture, such as that presented in Kynaston McShine’s famous exhibition Primary Structures earlier that year at the Museum of Modern Art.[4] [5]

Excerpt from the text Eccentric Abstraction by Verena Kittel. See full version in the publication Invitations, Spector Books, 2020.

[1] Lucy R. Lippard, “Landmark Exhibitions Issue. Curating by Numbers,” Tate Papers, issue 12 (2009): 1.

[2] See Owen Hulatt, ed., Aesthetic and Artistic Autonomy (London: Bloomsbury, 2013).

[3] Lippard had given lectures with the same title at the University of California, Berkeley, and at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art in the summer of 1966. Furthermore, she published a revised version of “Eccentric Abstraction” in, among others, Gregory Battock’s Minimal Art: A Critical Anthology in 1968 and in her own collection of essays Changing: Essays in Art Criticism in 1971.

[4] After working as a librarian from 1958 to 1960 following her graduation in art from Smith College, Lippard freelanced for MoMA as curator of traveling exhibitions and a writer. She was also involved in Primary Structures as a research assistant and befriended McShine. See Cornelia Butler, “Women – Concept – Art: Lucy R. Lippard’s Numbers Shows,” in From Conceptualism to Feminism: Lucy Lippard’s Numbers Shows 1969–74, ed.Cornelia Butler (Köln: Walther König, 2012), 19 f.

[5] Valeria Schulte-Fischedick criticizes the categorization of such practices labelled as postminimalism, anti-form, or process art by traditional historiography of post-war art into subcategories of, or as being developed in response to, minimal art, thereby reducing their impact. Working against juxtapositions of hard vs. soft, rigid/geometric vs. formless, formalism vs. personal or social subjects, which often resulted in male/female binaries seemingly inherent in such a reading, Schulte-Fischedick considers the formlessness of post-minimalism not as the female counterpart of minimalism, but as an independent exploration of form and tactile material surfaces, as part of a general interest in sensuality and sexual liberalization in the 1960s. See Schulte-Fischedick, “Something you bump into,” 10 ff.

Image: All images from this invitation are part of the Sammlung Marzona, Kunstbibliothek – Staatliche Museen zu Berlin.